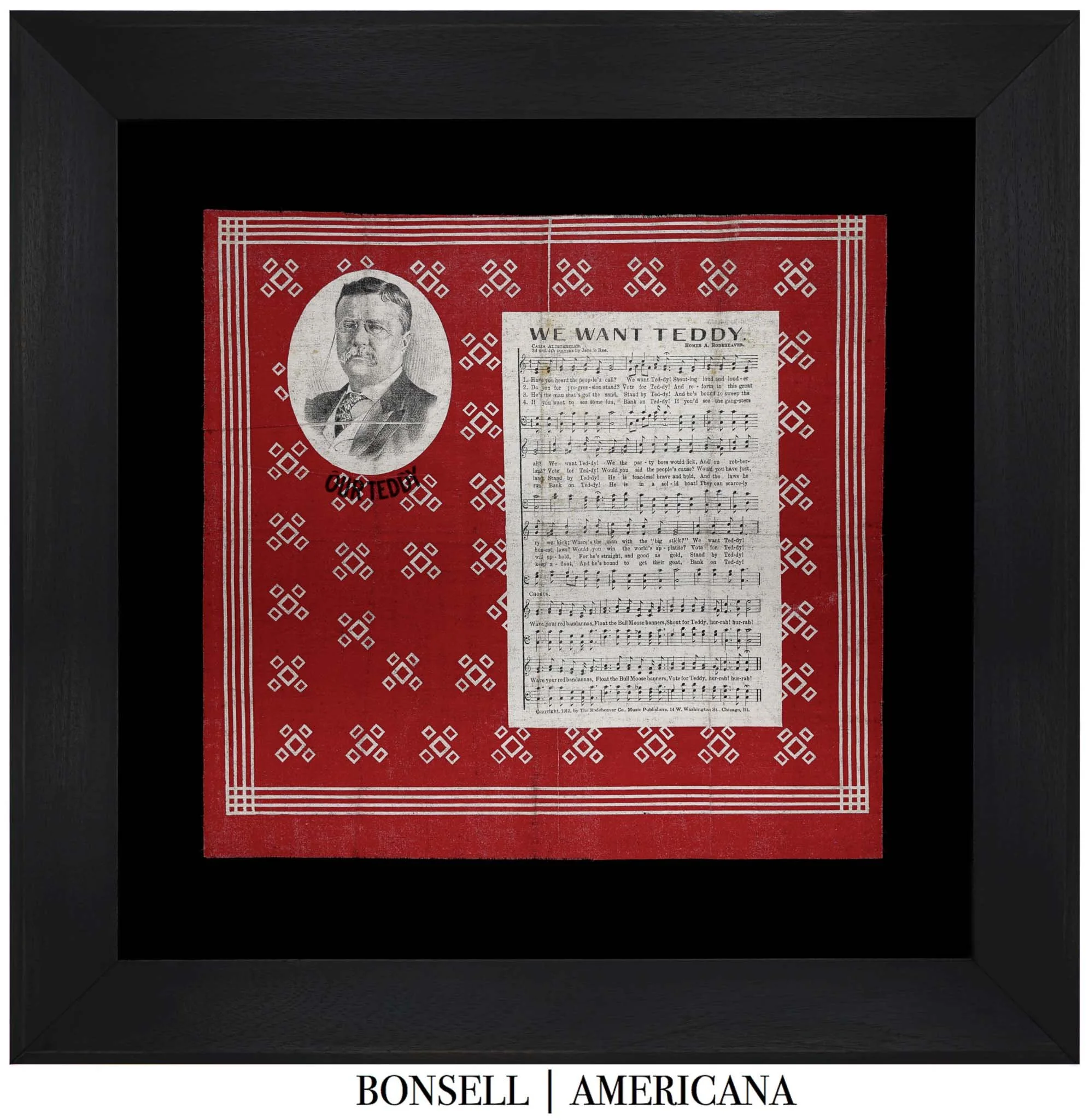

“We Want Teddy” Progressive Party Campaign Kerchief with Music | Bull Moose Movement | Circa 1912

“We Want Teddy” Progressive Party Campaign Kerchief with Music | Bull Moose Movement | Circa 1912

Frame Size (H x L): 28” x 28”

Kerchief Size (H x L): 18” x 18”

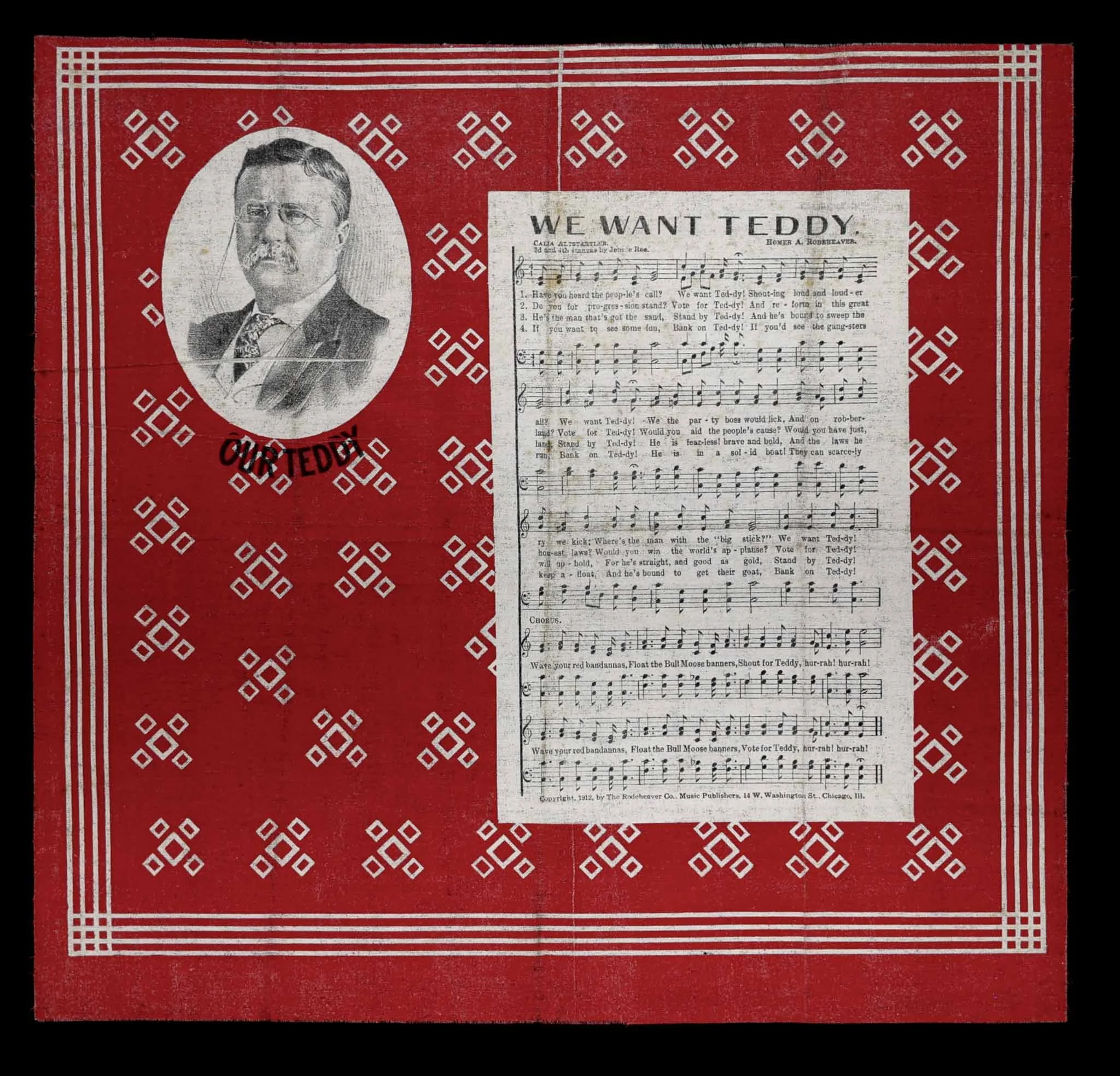

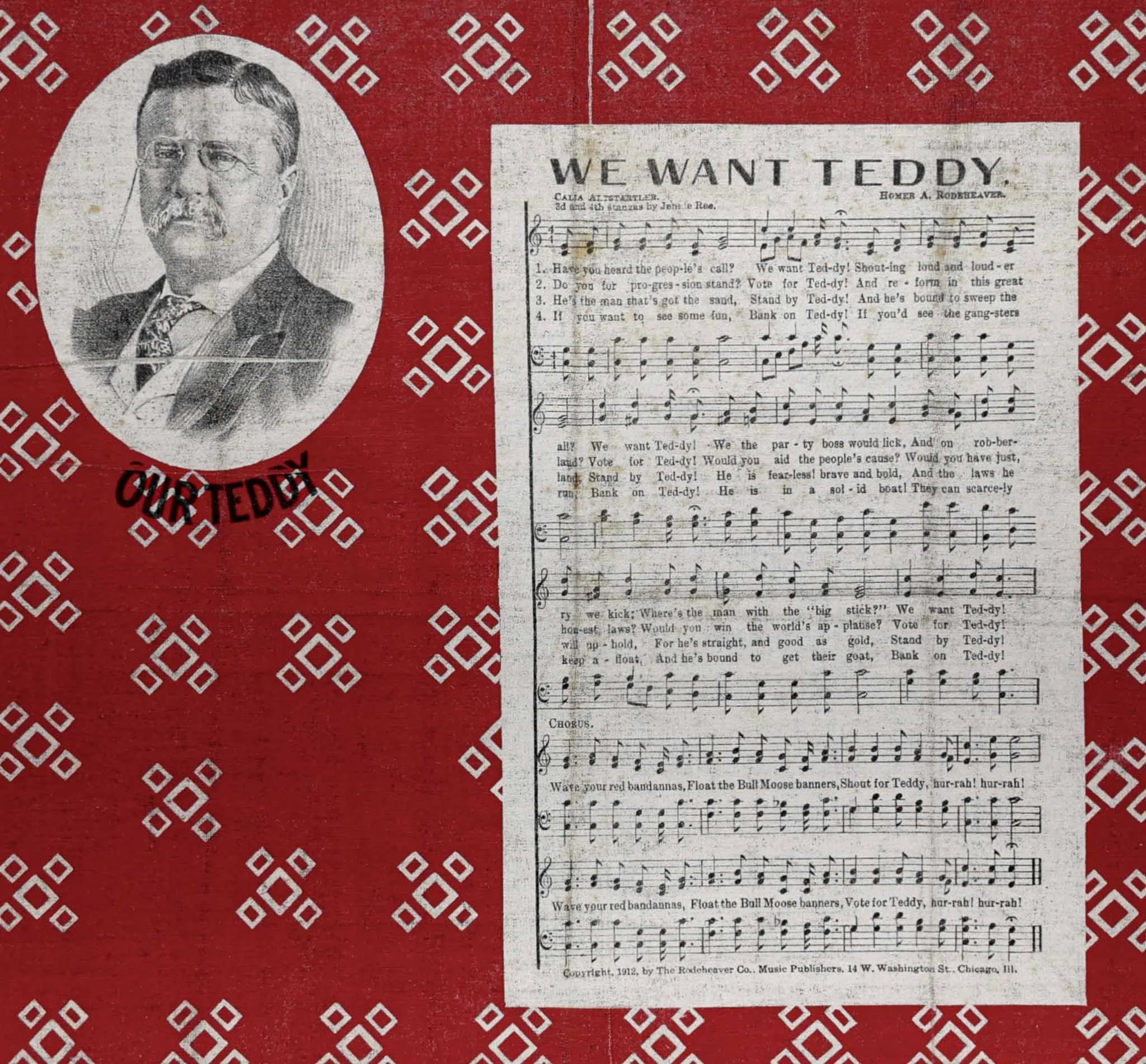

Offered is a rare Progressive Party campaign kerchief, produced in support of Theodore Roosevelt during the landmark 1912 presidential election. Printed in red on cotton, this textile belongs to a small but historically significant group of political bandannas that combined portraiture, text, and music to promote Roosevelt’s third-party candidacy during one of the most consequential elections in American history.

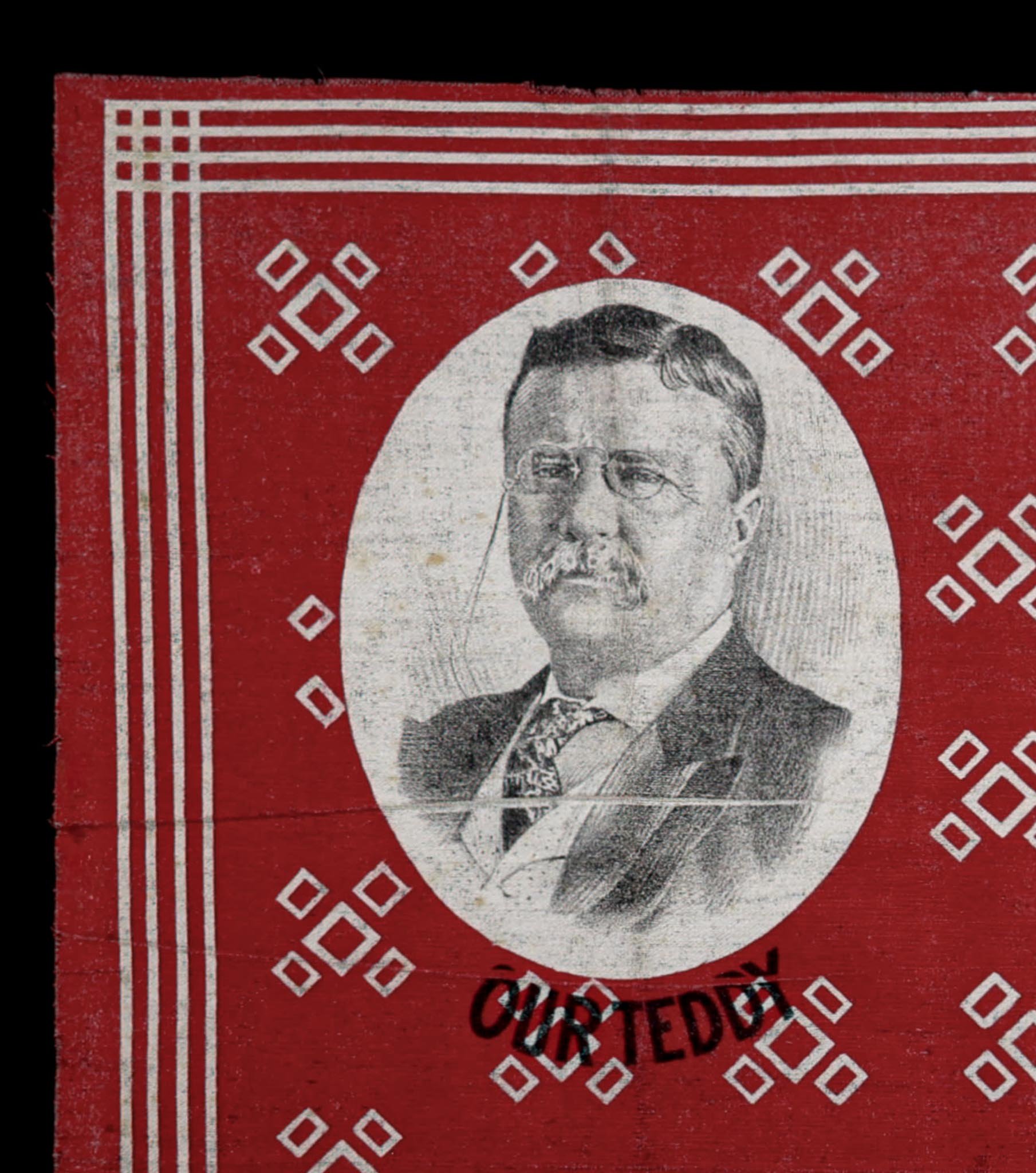

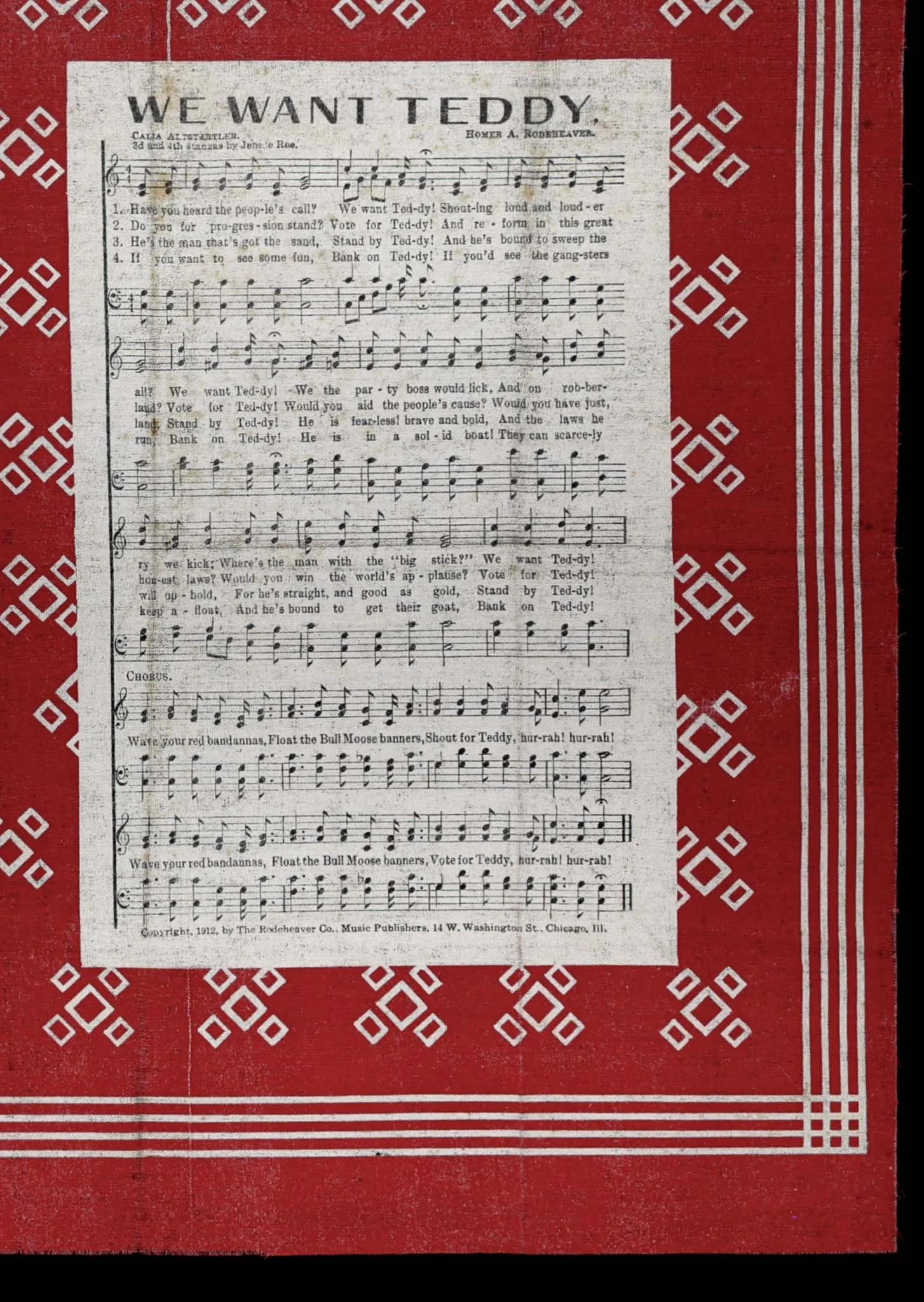

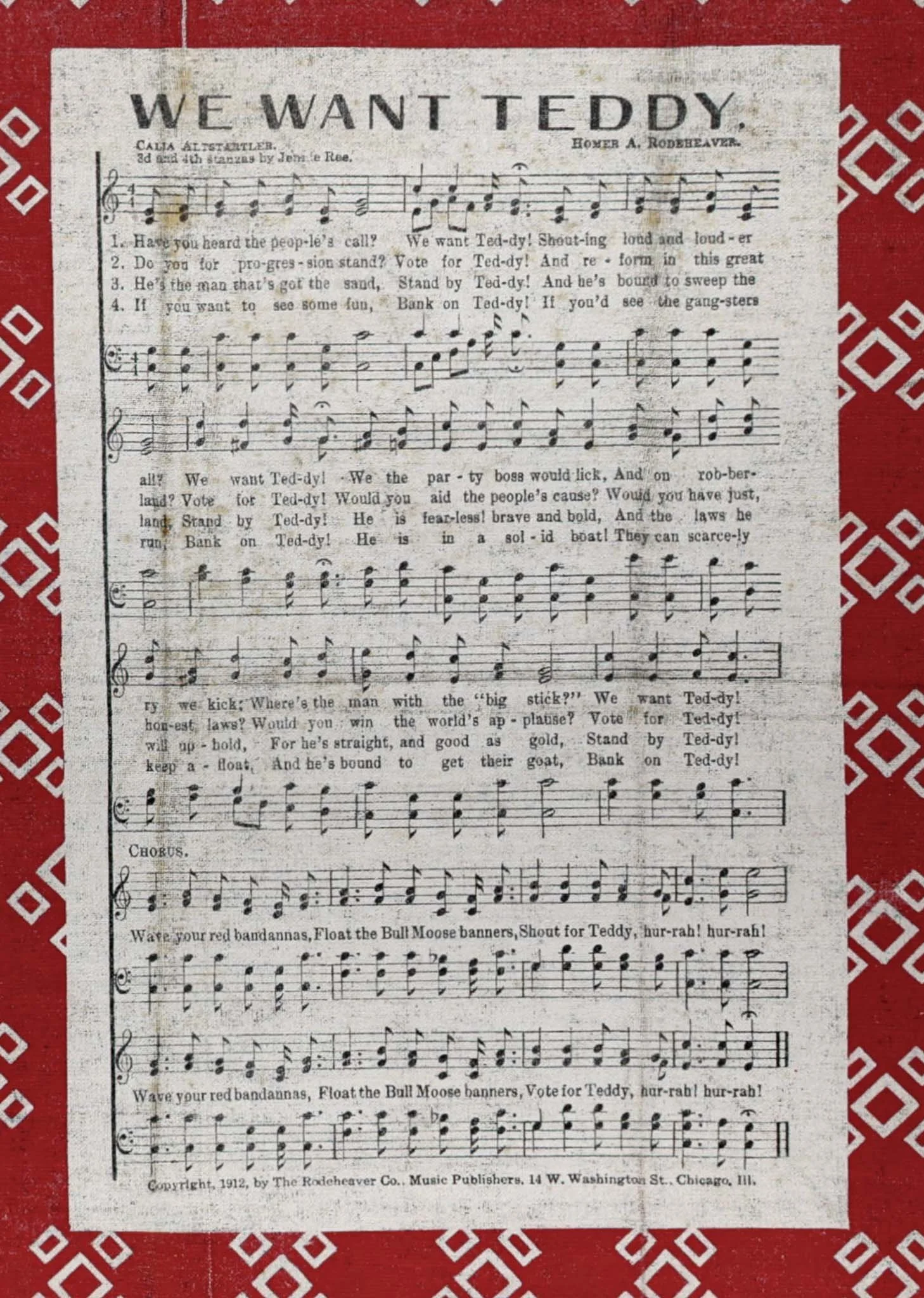

At left appears an oval portrait of Roosevelt, accompanied by the slogan “Our Teddy.” To the right is a printed sheet-music panel titled We Want Teddy, a campaign song closely associated with the Progressive movement. The lyrics reinforce Roosevelt’s reformist platform and make explicit reference to the Bull Moose Party, reflecting the populist enthusiasm and public engagement that characterized the campaign. The incorporation of musical notation directly into the design distinguishes this kerchief from more conventional graphic examples and illustrates the multi-layered approach to political messaging employed during the period.

The presence of the campaign song is significant. Music played a central role in early-20th-century American political culture, with songs written to be sung collectively at rallies, parades, and public gatherings. Here, the printed lyrics transform the kerchief from a purely visual object into an interactive one—meant to be read, sung, waved, or displayed. The straightforward language of the song mirrors the Progressive movement’s emphasis on mass participation and reform, while its integration with portrait and slogan demonstrates how image, text, and sound were deliberately combined to reinforce political identity. Political textiles incorporating music are comparatively uncommon, adding an additional layer of interest to this example.

The music panel also provides important documentary detail. The song We Want Teddy is credited to Homer A. Rodeheaver and carries a 1912 copyright. Publication is attributed to The Rodeheaver Company, located at 14 West Washington Street, Chicago, Illinois. Rodeheaver was a prominent figure in early-20th-century American music publishing, best known for his work in popular and religious song, and his involvement reflects the professional, commercial scale of music produced for the 1912 campaign. At the time, Chicago was a major national center for music publishing and printing, making it a logical base for the production and distribution of campaign songs intended for wide circulation.

The kerchief is printed on cotton, the standard fabric for campaign bandannas of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, selected for its durability, affordability, and suitability for large-scale production. The design was most likely executed using roller printing, a mechanized textile process widely employed at the time that allowed for consistent registration and the efficient reproduction of detailed imagery, including portraiture, text, and musical notation. Such methods made cotton kerchiefs effective vehicles for political messaging intended for broad public distribution.

This piece is directly associated with Roosevelt’s 1912 Bull Moose campaign, which followed his break with the Republican Party. Running as the Progressive Party candidate, Roosevelt advanced a platform he termed “New Nationalism,” calling for expanded federal authority to regulate corporations, protect labor, promote social welfare, and strengthen democratic institutions. His decision to run independently represented both a continuation of his earlier reformist policies and a response to what he viewed as the failure of his successor, William Howard Taft, to carry those policies forward.

The 1912 election marked one of the most significant fractures in American political history. After serving two terms, Roosevelt had pledged not to seek another, but growing dissatisfaction with Taft’s conservative approach—particularly regarding trust regulation—drew him back into national politics. When Roosevelt failed to secure the Republican nomination, he and his supporters formed the Progressive Party. Nicknamed the “Bull Moose Party” after Roosevelt declared himself “fit as a bull moose,” the movement became a clear expression of political independence and reformist resolve.

The Progressive platform advocated expanded labor protections, women’s suffrage, environmental conservation, and stricter federal oversight of corporate power—positions that set Roosevelt apart from both Taft and the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson. Although Roosevelt attracted substantial popular support, the divided Republican vote enabled Wilson’s victory. Roosevelt nonetheless carried 88 electoral votes to Taft’s 8, making the campaign the most successful third-party presidential effort in American history. While the Progressive Party itself was short-lived, its ideas exerted lasting influence on later reform movements, particularly those of the New Deal era.

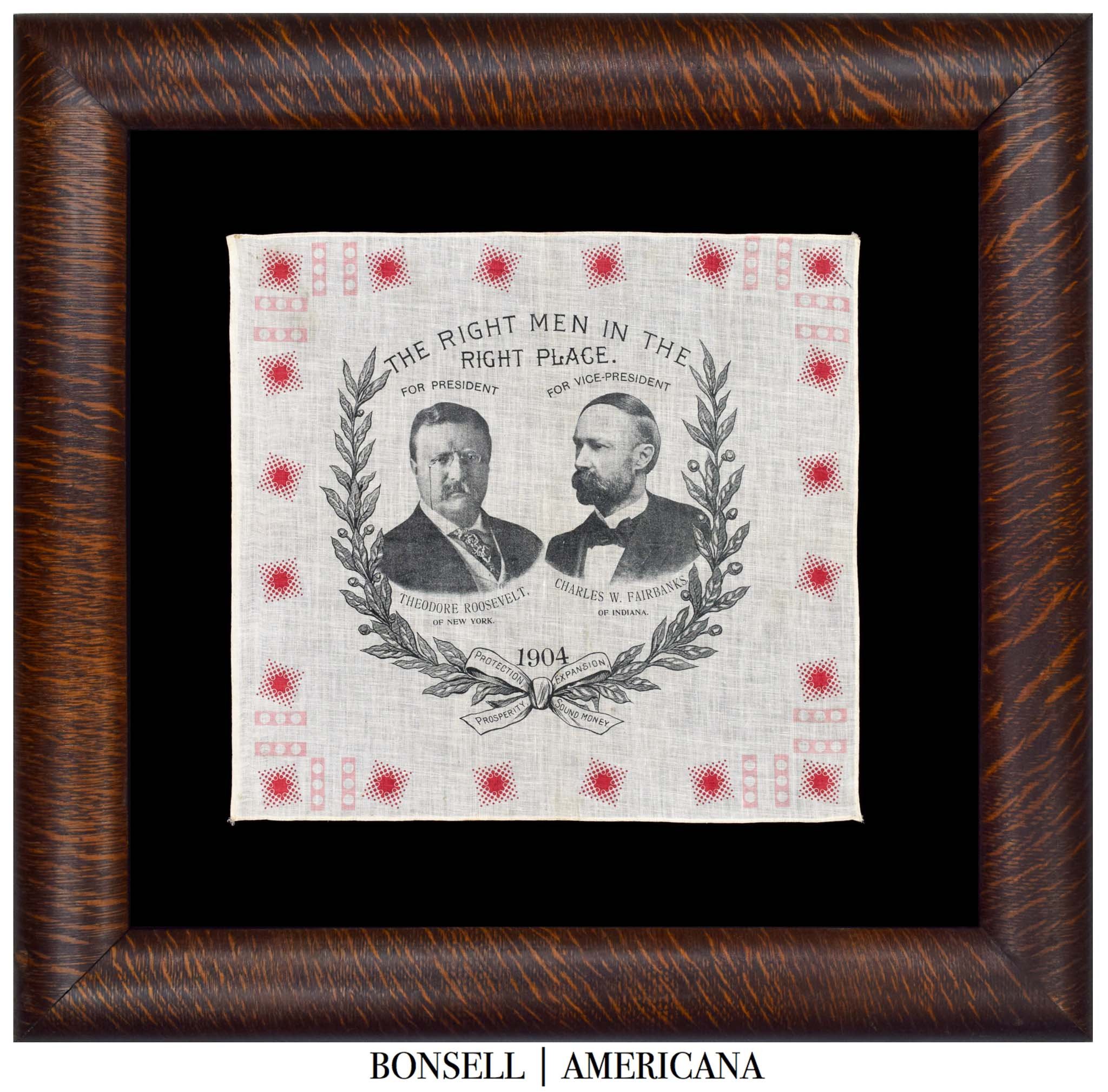

As documented in Threads of History, the portrait of Roosevelt is derived from a photograph taken by the Pack Brothers of New York in 1904, one of the leading portrait studios of the period. The reuse of a well-known formal photograph reflects common early-20th-century practice, in which established images were adapted for mass political dissemination. This exact design is illustrated and cataloged in Threads of History within the Ralph E. Becker Collection of the Smithsonian Institution, providing authoritative institutional confirmation of the kerchief’s design, imagery, and 1912 Progressive-era context.

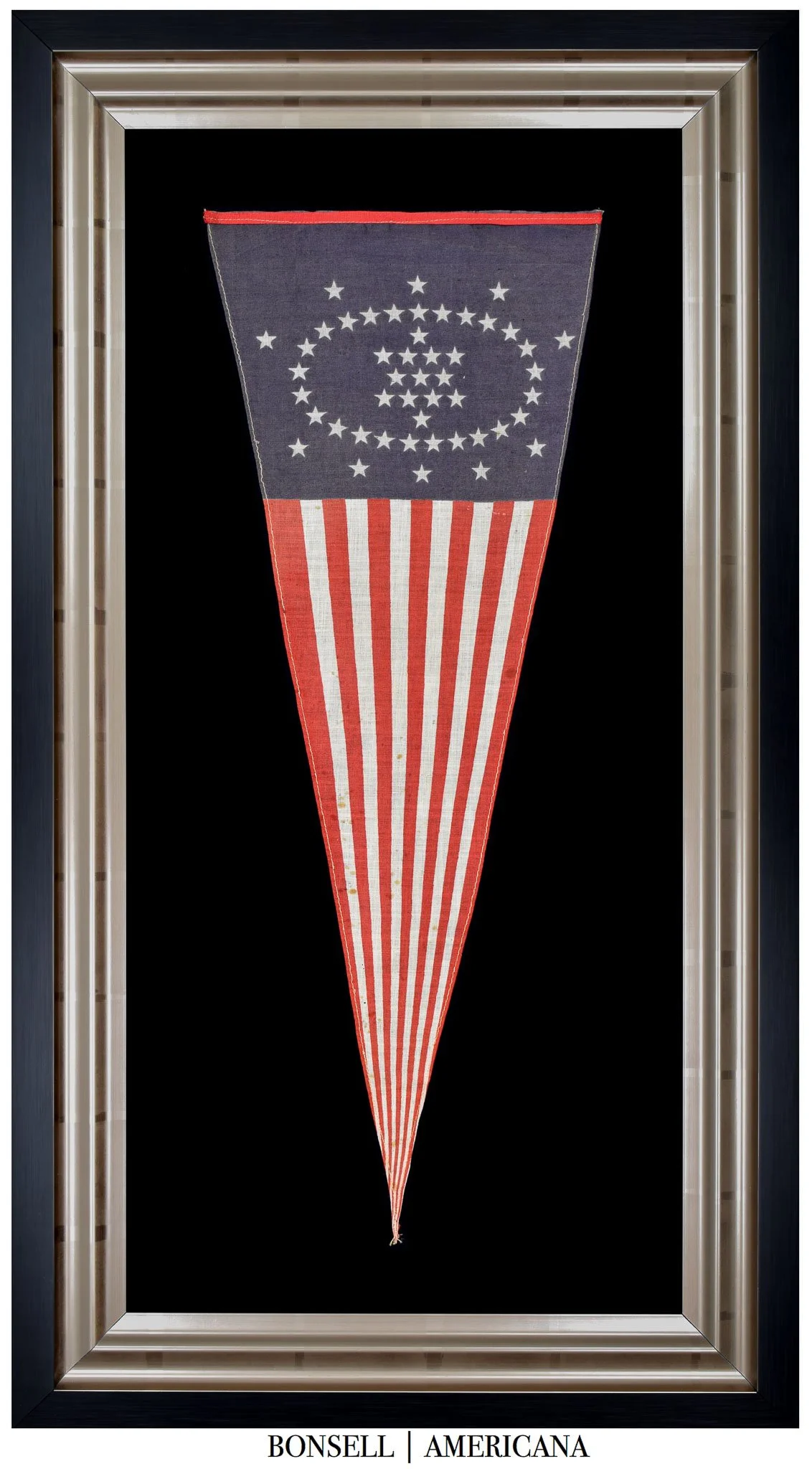

Political kerchiefs such as this were widely used as wearable symbols of support—worn by adherents, waved at rallies, displayed in storefronts, and retained as souvenirs of significant campaigns. Combining portraiture, slogan, music, and mass-produced textile technology, this example stands as a well-documented artifact of Progressive-era political culture and a surviving witness to one of the most consequential presidential elections in American history.

Conservation Process: This kerchief was hand sewn to cotton fabric, and both were hand sewn to a mounting board. To prevent the black dye in the cotton fabric from seeping into the kerchief, it was first washed in a standard wash and then in a dye setting wash. The kerchief is positioned behind Optium Museum Acrylic.

Frame: The kerchief is housed in a stained wood frame with a broad, sloped profile. The dark finish shows subtle tonal variation that allows the wood grain to remain visible. The profile provides strong visual containment while remaining understated and appropriate for period display.

Condition Report: Condition is good overall, with light surface soiling and scattered small spots or toning, most noticeable in the white areas of the portrait and music panel. The perimeter shows minor edge wear and slight fraying, consistent with age and use. There are no significant tears or losses.

Collectability Level: The Great – Perfect for Rising Collectors

Date of Origin: 1912