34 Star Civil War–Era American Flag | Adapted for the Garfield & Arthur Presidential Campaign | Dr. Jeffrey Kenneth Kohn Collection | Circa 1861–1863, Repurposed in 1880

34 Star Civil War–Era American Flag | Adapted for the Garfield & Arthur Presidential Campaign | Dr. Jeffrey Kenneth Kohn Collection | Circa 1861–1863, Repurposed in 1880

Frame Size (H x L): 33.25” x 61.5”

Overall Flag Size (H x L): 22” x 51.5”

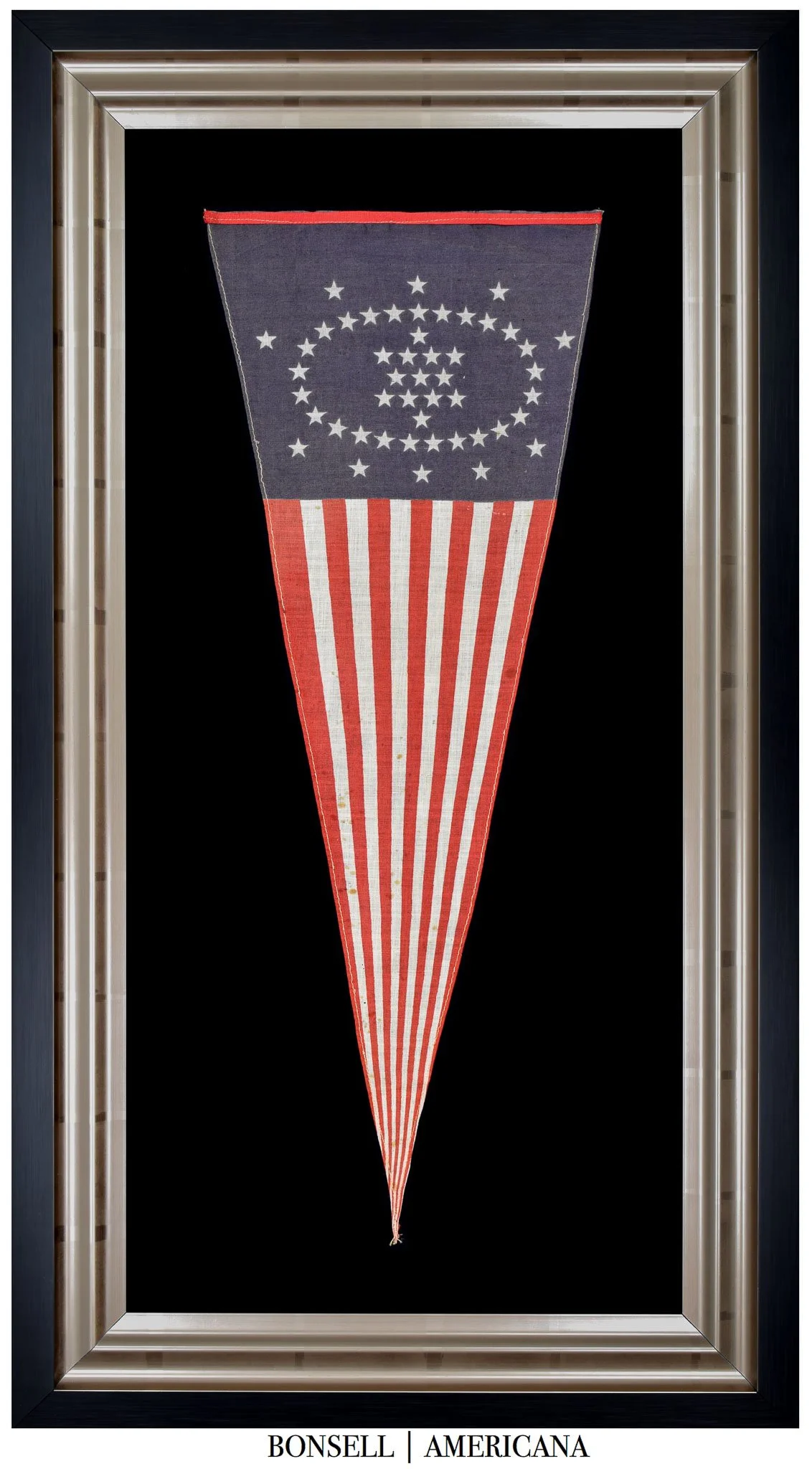

Offered is an outstanding 34-star American flag repurposed in 1880 to support the Republican presidential ticket of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. The flag’s body was produced during the early Civil War period, when Kansas entered the Union as the 34th state, and was later adapted for campaign use through the addition of a white cotton strip printed on each side with “GARFIELD AND ARTHUR.” The piece unites two defining moments in American history—the preservation of the Union and the political renewal of the postwar Republic.

The flag’s body measures approximately 22 by 46 inches, excluding the added campaign strip, which brings the full length to about 51.5 inches overall. It displays 34 press-dyed stars arranged in a rare 8-1-8-8-1-8 configuration. The proportions are elongated and the design distinctly folk, suggesting small-shop or regional manufacture rather than factory production. The star pattern, with its two offset outliers near the hoist, lends the canton a lively sense of movement, departing from the rigid grids typical of printed parade flags.

CONSTRUCTION

The red-and-white field is one continuous length of woven cotton, not pieced or printed. The alternating stripes were produced at the loom by alternating red-dyed warp threads with undyed (white) warps across the beam, while the weft remained white throughout. The red color is therefore structural, derived from the yarn itself rather than applied pigment. Where the red and white warp groups meet, the colors blend softly, creating subtle transitions characteristic of mid-19th-century striped cottons.

This warp-dyed “colored sheeting” was a staple product of American mills in the 1850s and 1860s, made by dyeing warp yarns in Turkey-red or madder baths before weaving. Combined with plain white weft, the process yielded finished yard goods ideal for flag production and removed the need for pieced stripes or surface printing in many cases. The fabric’s slightly coarse, wool-like texture results from short-staple cotton fibers, uneven spinning, and residual starch sizing applied for loom stability—features typical of patriotic bunting of the era.

The blue canton is made of a separate piece of undyed cotton, hand-sewn to the striped field with small whipstitches visible along the inner edge. Its coloration was achieved by press-dyeing, a resist-dye process in which star forms were masked with a wax or paste compound before the fabric was pressed between dye-soaked pads or immersed under pressure in a blue dye bath. When the resist was removed, undyed stars remained against a deep matte blue ground. The blue pigment penetrates evenly through the cloth, producing soft feathering along the star edges rather than the crisp mechanical borders of roller printing.

The hoist consists of a separately applied band of plain-weave cotton, folded and hand-stitched to the canton and field with heavy cotton thread. The pair of small circular apertures, near the top and bottom, are hand-worked and reinforced with thread, not fitted with a metal grommet. Along the hoist appear inked notations reading “22 × 46” and “–CX2,” the latter preceded by a faint, indecipherable character. The marks were applied in the same hand and ink, likely by the original maker to indicate dimensions and batch or pattern identification.

At the fly end, a white cotton strip approximately five and a half inches wide was added during the 1880 campaign. The fabric differs markedly from the main field—finer in weave and with a subtle calendered finish intended to accept ink evenly. It was attached by a straight, machine-sewn line of undyed cotton thread, executed with the precision and tension consistency typical of a treadle sewing machine. The seam is nearly invisible today, as both thread and fabric have aged to the same pale ivory tone. After attachment, the legend “GARFIELD AND ARTHUR” was stenciled by hand in black oil-based pigment. The pigment penetrates fully through the fibers, showing minor haloing and variation in opacity from letter to letter. Its oxidized gray tone and lack of embossing confirm a brush or pad application through a cut stencil rather than mechanical printing.

Taken together, these details reveal a flag produced in 1861 to 1863 for patriotic display, later reissued circa 1880 as a campaign banner.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

The 34-star flag officially represented the United States from July 4, 1861, to July 3, 1863, commemorating Kansas’s admission to the Union. It flew during the first two years of the Civil War, a period marked by uncertainty, sacrifice, and the forging of a new national identity. By 1880, such flags were already antiquated, yet their presence remained familiar. Merchants and campaign committees occasionally repurposed Civil War–era stock by printing or sewing candidate names across surviving examples. In some cases, this was an intentional gesture—an effort to evoke wartime unity and the victory of the Union cause. In others, it was a matter of simple pragmatism: the ready availability of leftover flags and bunting from earlier decades made them a natural choice for campaign display.

The Garfield–Arthur ticket arose from a deeply divided Republican Party. In the aftermath of Reconstruction, the party fractured between reformers who sought to curb political patronage and traditionalists who defended the existing system. When the Republican National Convention deadlocked between Ulysses S. Grant and James G. Blaine, delegates turned to James A. Garfield of Ohio, a respected former Union general, scholar, and nine-term congressman, as a compromise nominee. To balance the ticket, they selected Chester A. Arthur of New York, an ally of the powerful party machine led by Roscoe Conkling.

The 1880 campaign emphasized national unity, economic growth, and the moral integrity of Republican leadership. Garfield’s image as a self-made man—born in a log cabin, educated through sheer persistence, and rising from canal laborer to college president—resonated with voters still drawn to the ideal of the citizen-soldier. His war service at Shiloh and Chickamauga lent authenticity to his calls for stability and reconciliation. By contrast, Democratic nominee Winfield Scott Hancock, also a Union general and war hero, made the race unusually close, with both candidates celebrated for their military valor.

Garfield and Arthur ultimately prevailed by one of the narrowest popular margins in U.S. history—a difference of just about 10,000 votes nationwide—but secured a comfortable 214 to 155 victory in the Electoral College. Their triumph reaffirmed the Republican Party’s national dominance in the postwar era and its identification with Union loyalty and progress.

Garfield’s presidency, however, was tragically brief. Barely four months after his inauguration, he was shot by a disgruntled office seeker, Charles Guiteau, and died eleven weeks later, in September 1881. The event shocked the nation and stirred widespread disgust with the patronage system that had divided the party. Chester A. Arthur, long viewed as a machine politician, ascended to the presidency amid skepticism but soon surprised the public by embracing civil service reform, signing the Pendleton Act in 1883 and earning an enduring reputation for integrity and restraint.

Against that backdrop, this flag stands as a poignant emblem of the political and cultural crosscurrents of its age—a Civil War–era banner literally reborn for the campaign that would reshape the Republican Party and usher in the modern civil service system. Whether reused deliberately to recall Union victory or simply drawn from surviving stock, its adaptation links two defining eras in American history: the struggle for national preservation and the postwar effort to reform and reunify the nation.

PROVENANCE

This example originates from the collection of Dr. Jeffrey Kenneth Kohn, M.D., one of the country’s foremost authorities on historic American flags. Dr. Kohn began collecting in the early 1980s, assembling one of the most comprehensive private holdings of 19th-century flags and patriotic textiles. A respected historian and lecturer, he served as Historian for the Philadelphia Flag Day Association, curated major flag exhibitions at the Union League and Betsy Ross House, and co-authored American Flags: Designs for a Young Nation. His expertise in textile analysis, manufacturing techniques, and period dye processes has informed museum collections nationwide. The association with his collection underscores this flag’s authenticity and importance within the broader field of American political textiles.

SIGNIFICANCE

In both construction and historical resonance, this flag offers a remarkably complete picture of American textile and political culture in transition. Its woven red and white stripes, press-dyed canton, hand-sewn hoist, machine-stitched campaign strip, and stenciled inscription together embody two generations of craftsmanship—one rooted in hand production, the other in emerging industrial methods. Each layer reflects a different chapter of the national story: the technical ingenuity of mid-19th-century cotton mills, the artistry of resist dyeing, the rise of mechanical sewing, and the enduring impulse to reinterpret patriotic symbols through political expression.

The survival of all these elements, unaltered and intact, makes this one of the most compelling known Garfield & Arthur campaign flags.

Conservation Process: The flag was hand sewn to cotton fabric, and both were hand sewn to a mounting board. To prevent the black dye in the cotton fabric from seeping into the flag, it was first washed in a standard wash and then in a dye setting wash. The flag is positioned behind Optium Museum Acrylic.

Frame: The flag is presented within a hardwood frame finished in matte black with visible grain.

Condition Report: The flag displays strong overall integrity, with the fabric stable and the colors in the canton and stripes still well defined. Expected signs of age are present, including minor fabric thinning, small losses along portions of the red stripes, and light wear at the upper edge. The “GARFIELD AND ARTHUR” printing shows fading and surface wear, yet remains legible. The weave throughout the textile is sound and tightly set.

Collectability Level: The Best – Perfect for Advanced Collectors

Date of Origin: 1861-1863, Repurposed 1880

Number of Stars: 34

Associated War: The Civil War (1861-1865) and the Indian Wars (1860-1890)

Associated State: Kansas