38 Star Parade Flag with a Grand Luminary Configuration and Gold Fringe | Rare Ceremonial Example Linked to Lincoln’s Funeral in Philadelphia | Circa 1865

38 Star Parade Flag with a Grand Luminary Configuration and Gold Fringe | Rare Ceremonial Example Linked to Lincoln’s Funeral in Philadelphia | Circa 1865

Price: Call 618-553-2291, or email info@bonsellamericana.com

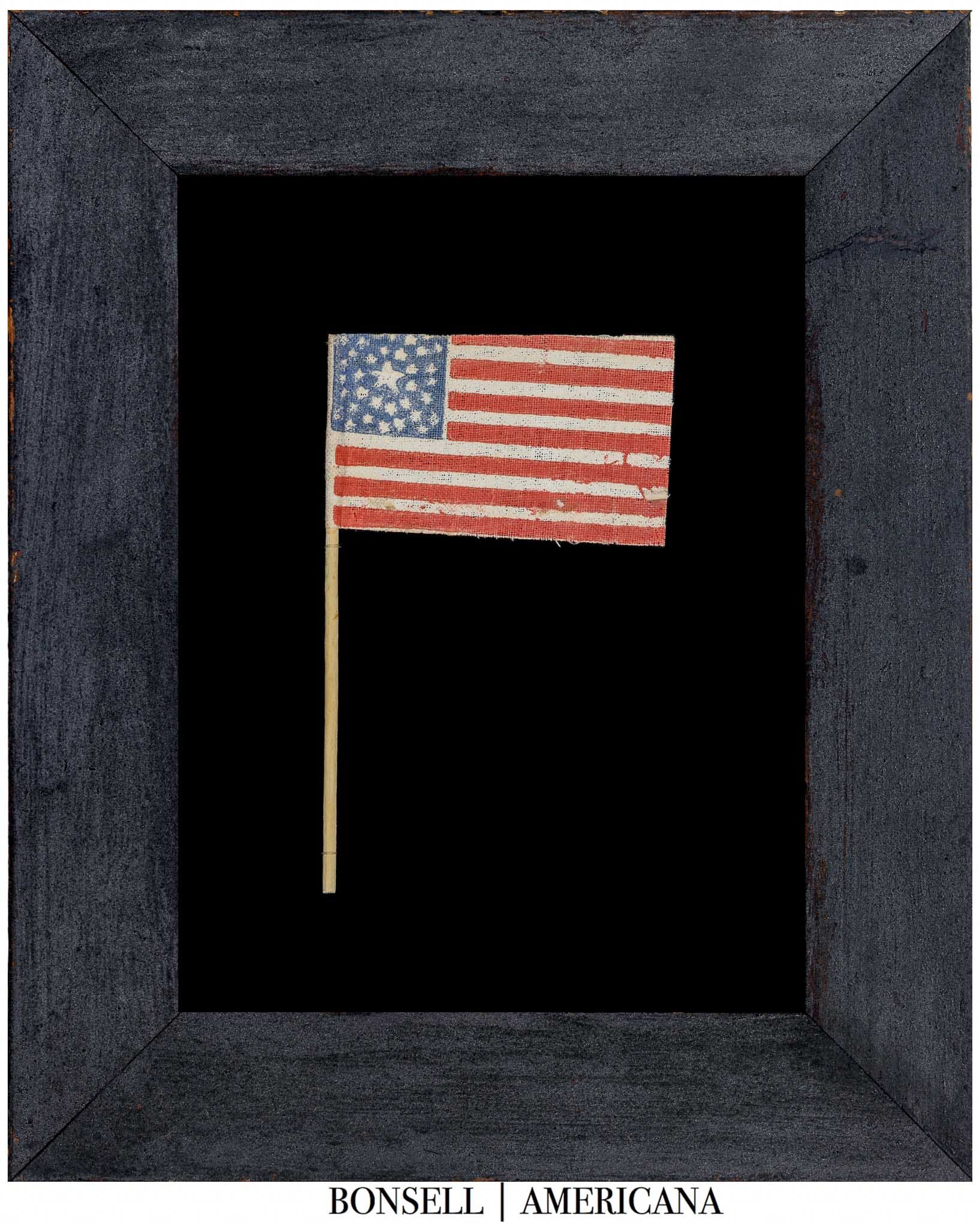

Frame Size (H x L): 16.75” x 12.75”

Flag Size (H x L): 5.5” x 6.75” and Affixed to a 10.5” Staff

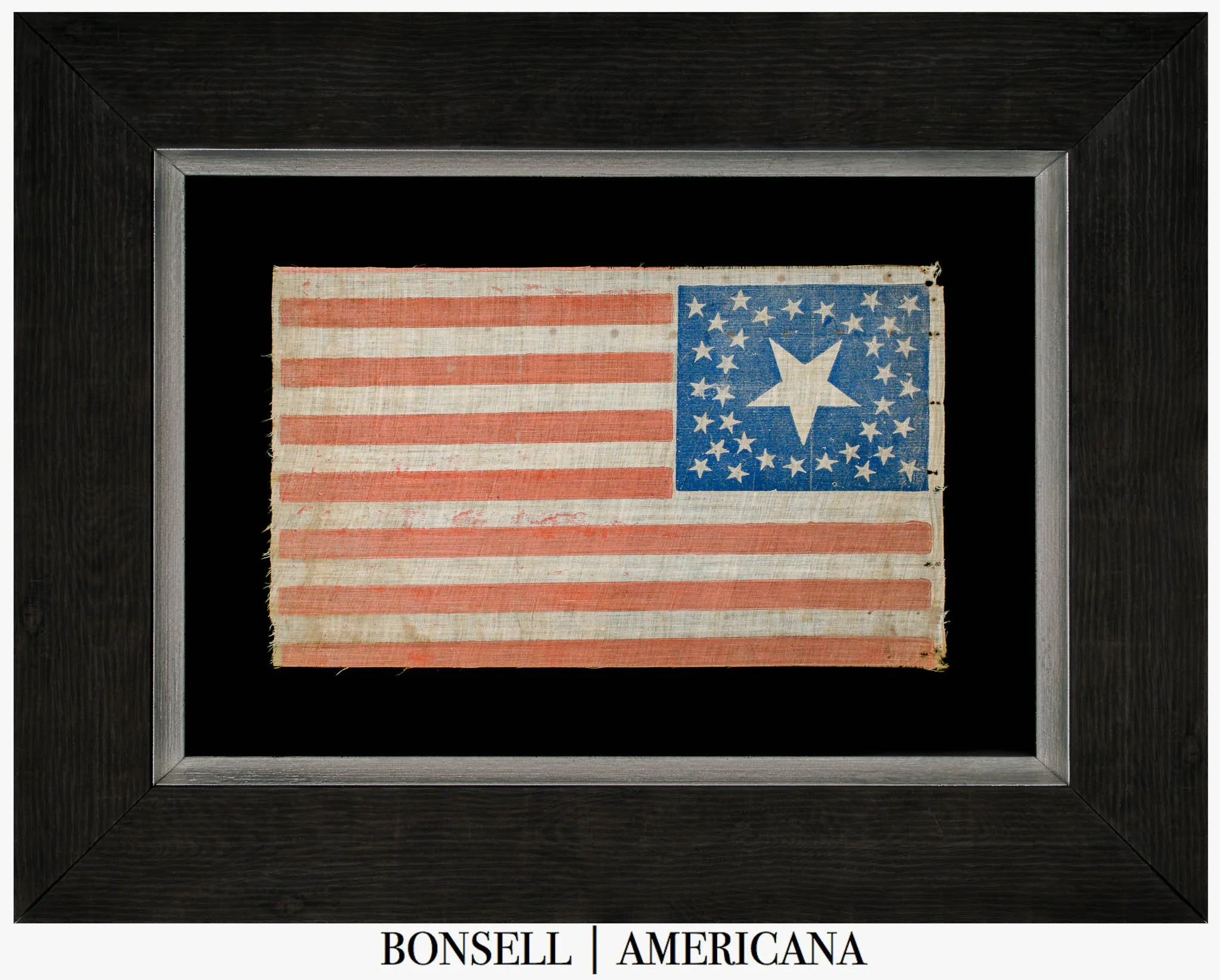

Offered is a 38-star American parade flag, printed on fine silk, bordered on three sides with gold fringe, and mounted to its original turned-wood staff with a smooth finish, gilt spear finial, and sharpened lower point. The stars are arranged in a Great Star—or Great Luminary—pattern, consisting of 34 stars forming the larger star and four flanking stars in the corners.

The flag’s construction and finish indicate use in a formal or ceremonial context. The printed silk, gold fringe, and carefully finished staff are consistent with patriotic and commemorative flags produced in Philadelphia and other major cities during the mid-nineteenth century.

THE FLAG

This small silk flag was printed with precise registration and even coloration, the stripes sharply defined and the canton evenly inked. The silk’s fine weave and sheen reflect a quality consistent with high-end commercial production. The flag remains attached to its original turned-wood staff by two small nails driven through the hoist—an attachment method typical of finer ceremonial flags, providing a secure but discreet means of fastening while preserving the textile’s presentation.

The gold fringe, sewn by hand along three sides, was reserved for interior and commemorative use. The smooth, turned staff with gilt finial and sharpened point suggests the flag was intended for formal display rather than outdoor procession. The combination of materials and finish places it among the more refined small-format silk parade flags of its period.

THE GREAT STAR PATTERN

The Great Star, or Great Luminary, pattern arranges smaller stars into the form of a single large five-pointed star, representing the idea that many states together form one nation. The design is credited to U.S. Naval Captain Samuel Chester Reid (1783–1861), a veteran of the War of 1812 and longtime harbor master of New York. Reid gained public recognition for his defense of the privateer General Armstrong at the Azores in 1814—an engagement that delayed the British fleet bound for New Orleans—and later became known for his expertise in maritime signals and his advocacy for a more standardized approach to American flag design.

In early 1818, as Congress debated how to revise the expanding and cumbersome fifteen-stripe flag created under the 1794 act, Reid corresponded with Representative Peter Wendover of New York and proposed a simplified system: thirteen stripes to honor the founding colonies and one star for each state, arranged in a coherent geometric form. Among several suggested layouts, Reid’s preferred design placed the smaller stars into the shape of a single large star—“a constellation within a constellation”—to convey unity and legibility at distance, particularly at sea.

Although the resulting Flag Act of 1818 adopted Reid’s principle of thirteen stripes and one star per state, it did not legislate any specific star pattern, leaving the arrangement to individual makers. The Great Star, however, quickly became one of the most admired and enduring designs of the nineteenth century. It appeared on printed parade flags, campaign banners, and naval ensigns, valued for its symmetry and balance.

By the time of the Civil War, the Great Star carried both historical and patriotic associations. It was viewed as a traditional pattern linking the modern Union to the ideals of the early Republic. Flag makers continued to employ it for ceremonial and commemorative use, particularly on fine silk parade flags and memorial banners. In this example, 34 stars form the large central figure, while four stars placed beyond the points complete the count of 38, producing a bold and symmetrical display consistent with the best mid-century printed examples.

ANTICIPATORY MANUFACTURE

The 38-star count corresponds to Colorado’s admission to the Union on August 1, 1876, though this star count did not become official until July 4, 1877. During the nineteenth century, flag makers frequently issued new designs before formal adoption, anticipating the next state to enter the Union.

This practice of pre-admission manufacture was both commercially practical and culturally symbolic. It allowed printers to offer “updated” flags immediately after statehood while reflecting public optimism about westward expansion. Comparable anticipatory flags exist for earlier admissions, including Kansas (1861) and Nevada (1864).

Colorado’s path to statehood began well before 1876, with petitions for admission introduced as early as 1864, during the Civil War. Congress debated its admission repeatedly over the following decade, and newspapers in eastern cities, including Philadelphia, reported on its prospects alongside those of Nebraska and Nevada. The anticipation of new western states encouraged flag makers to prepare designs reflecting expanded star counts.

By the mid-1860s, Philadelphia had become one of the nation’s foremost centers for patriotic manufacture. Firms such as Annin & Co., Horstmann Brothers, and numerous smaller print shops along Chestnut and Market Streets produced silk and cotton parade flags in a range of star configurations, often ahead of official adoption. These companies marketed their goods for parades, civic events, and military ceremonies, where flags bearing more than the current official number of stars were common symbols of national growth and optimism.

Within this commercial environment, a 38-star flag printed in the 1860s would not have been unusual. The practice of speculative printing—producing new star counts in expectation of future admissions—was routine. The combination of silk fabric, applied gold fringe, and finished wooden staff seen here reflects the upper tier of that market: a ceremonial-quality flag made for display rather than distribution. Such details are consistent with the craftsmanship of Philadelphia’s mid-century flag and military outfitters and with the city’s role as a major supplier of patriotic materials during and immediately after the Civil War.

CEREMONIAL AND MEMORIAL USE

Flags of this type were made for civic and commemorative display, not mass distribution. During the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, small silk flags with fringe were used to decorate interior spaces, honor guards, and funeral settings.

In the days following Lincoln’s assassination, cities across the Union displayed mourning drapery and American flags. In Philadelphia, the ceremonies of April 1865 made extensive use of flags and banners, both in the procession and in the interior of Independence Hall. Surviving period descriptions mention flags arranged around the casket and within the Assembly Room.

The materials and construction of this flag correspond closely to that setting. The quality of printing, the fringe, and the fine staff align with the decorative standards of funeral and memorial display rather than the rougher cotton handwavers distributed to the public.

PROVENANCE AND DOCUMENTATION

A typed and signed affidavit dated November 1, 1934, accompanies the flag. It was written by Louis Irving Reichner (1871–1942) of Philadelphia, a lawyer and genealogist. In the statement, Reichner records that his grandmother, Eliza J. Stephens, was present in Independence Hall during the removal of Lincoln’s remains on April 24, 1865, and that a soldier guarding the casket gave her one of the American flags placed around it.

The affidavit’s content and dates correspond exactly to the documented record of Lincoln’s funeral. A certified Philadelphia birth record, issued in 1918, confirms Reichner’s birth on July 14, 1871, to Louis Reichner, Jr. and Christiana (Stephens) Reichner, verifying his descent from Eliza J. Stephens.

Both the affidavit and birth certificate were found in Reichner’s personal Bushnell’s “Paperoid” expanding wallet, manufactured by the Alvah Bushnell Company of Philadelphia and gilt-stamped “L.I.R. / Life Ins.” The wallet retains its original paper envelope and maker’s printed insert.

Reichner’s obituary (1942) records a long and accomplished career. Born in Philadelphia in 1871, he attended the William Penn Charter School before earning degrees from Princeton University (M.A., 1897) and the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Following admission to the bar, he joined the Fidelity Trust Company in Philadelphia, where he worked in the trust and estate division before entering private practice. By 1910 he had become associated with the firm of Duane, Morris & Heckscher, one of the city’s oldest and most respected law offices, known for its corporate and banking clientele. In 1926 he accepted a position in New York as counsel for the National Properties Corporation, continuing to specialize in trust and real-estate matters.

During the First World War, Reichner served as a Captain in the U.S. Army Ordnance Department, responsible for procurement and supply logistics. He was promoted to Major in the Reserve Corps in 1919 and later to Lieutenant Colonel in 1929, remaining active in military reserve service into the 1930s.

Beyond his professional work, Reichner was deeply involved in civic and cultural organizations. He was a founding member and officer of the Princeton Club of Philadelphia, a long-time participant in the Orpheus Club, and a member of the Sons of the Revolution, the Society of the War of 1812, and the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania. These affiliations reflect both his social standing and his enduring interest in American history and lineage. His involvement in genealogical and patriotic societies, coupled with his training as a lawyer, made him unusually well suited to document family history with care and precision—an aptitude reflected in the 1934 affidavit that accompanies this flag.

LINCOLN’S FUNERAL IN PHILADELPHIA

When the funeral train carrying Abraham Lincoln’s remains left Washington on April 21, 1865, it began a twelve-day journey to Springfield, Illinois. The Philadelphia stop was among the most elaborate and most attended of the entire route.

The train arrived at the Broad Street Station on Saturday, April 22. The casket was transferred to a hearse draped in black, drawn by eight gray horses, and escorted by city officials, soldiers, and members of the fire companies. The procession moved north on Broad Street and east along Chestnut toward Independence Hall. Contemporary reports describe a silent crowd and buildings covered in mourning cloth.

A correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune (April 24, 1865) noted the depth and decorum of the city’s mourning: “The good taste of the citizens of Philadelphia was displayed in the mourning habiliments of their dwellings and places of business yesterday to-day, as well as during the entire week. Among the most prominent were the residences of Gens. Grant and Meade, which were covered with flags festooned with crape. Numerous military officers have their headquarters in Girard-st., and they are beautifully draped. The ladies appear with mourning badges on their left shoulders, and this custom had become so general that its non-observance is noticed.”

Inside the Assembly Room of Independence Hall, the coffin was placed on a raised platform. Soldiers stood guard as thousands filed past. The room was decorated with floral wreaths, patriotic emblems, and heavy black drapery.

A front-page engraving in the Philadelphia Inquirer (April 25, 1865), titled “President Lincoln’s Remains in Independence Hall,” depicts the scene. In the image, the bier stands in the center of the chamber beneath swags of bunting and banner-shaped hangings that fill the background. While discrete small hand-held flags are not identifiable, the décor includes flag-like folds and shield emblems that convey the patriotic symbolism described in contemporary accounts. The National Park Service, drawing from period descriptions, similarly notes that the Assembly Room was “adorned in mourning from floor to ceiling” as approximately 100,000 (or more) mourners filed past over twenty hours of visitation.

Public viewing began on the evening of April 22 and continued through Sunday, April 23. At dawn on Monday, April 24, the casket was closed and borne again to a hearse under escort of soldiers and firemen for transport to the depot. Although the departure took place before sunrise—around four o’clock in the morning—large crowds gathered once more along Chestnut and Broad Streets to pay their final respects. Contemporary accounts describe men, women, and children standing in silence as the hearse passed, church bells tolling in the distance, and flags lowered throughout the city. The train departed amid this quiet vigil, beginning the next stage of its journey to New York.

Reichner’s 1934 affidavit, written nearly seventy years later, aligns closely with these records: his grandmother’s presence on the day of removal, the guard stationed beside the casket, and the presence of American flags among the decorations. While no contemporary photograph of such flags survives, the affidavit’s details correspond precisely to the documented sequence of the Philadelphia ceremonies and to the known decorative traditions of that event.

SIGNIFICANCE

This flag and its documentation form a coherent and verifiable group. The flag itself is a fine example of small-format silk printing from the mid-nineteenth century, made with quality materials suited for ceremonial use. Its 38-star Great Star pattern reflects both patriotic symbolism and the practice of anticipatory manufacture.

The supporting documents—the affidavit, birth record, and personal wallet—create an unbroken chain of ownership from an eyewitness at Lincoln’s funeral to her grandson, who recorded and preserved the story. The group provides unusually complete provenance for an object of this nature and situates it clearly within the broader context of American mourning and civic commemoration in 1865.

Taken together, these materials represent a rare survival linking a known family witness to one of the most important public ceremonies in nineteenth-century American history.

Conservation Process: This flag was professionally conserved. It is sewn to silk and positioned behind Optium Museum Acrylic.

Frame: The frame is a circa 1900 hand-carved wood example with a dark-stained finish and excellent corner joints. It features a repeating leaf-and-stem motif and a gilt-painted inner liner that provides a simple, period-appropriate contrast. Solidly constructed and well-preserved, it is typical of quality American craftsmanship from the early 20th century.

Condition Report: The flag shows moderate signs of age and use consistent with its period. The silk remains intact with some scattered stains, light surface soiling, and minor splits visible under magnification. The colors are strong for its age, with the red slightly muted and the blue well preserved. The gold fringe and staff remain firmly attached and in stable condition.

Collectability Level: The Extraordinary – Museum Quality Offerings

Date of Origin: 1865

Number of Stars: 38

Associated War: The Civil War (1861-1865)

Associated State: Colorado