Important 13 Star Silk Presentation Flag | Made by Betsy Ross’s Great-Granddaughter Mary Catherine Robison | In Memory of Colonel Simon W. Scott | Circa 1906

Important 13 Star Silk Presentation Flag | Made by Betsy Ross’s Great-Granddaughter Mary Catherine Robison | In Memory of Colonel Simon W. Scott | Circa 1906

Price: Call 618-553-2291, or email info@bonsellamericana.com

Frame Size (H x L): 41” x 59”

Flag Size (H x L): 29.5” x 47.25”

Offered is a hand-embroidered silk American flag inscribed in white thread along the hoist:

“In Memoriam – Simon W. Scott – First Pres. Washington Soc’y Sons American Revolution – Seattle July 20 – 1906.”

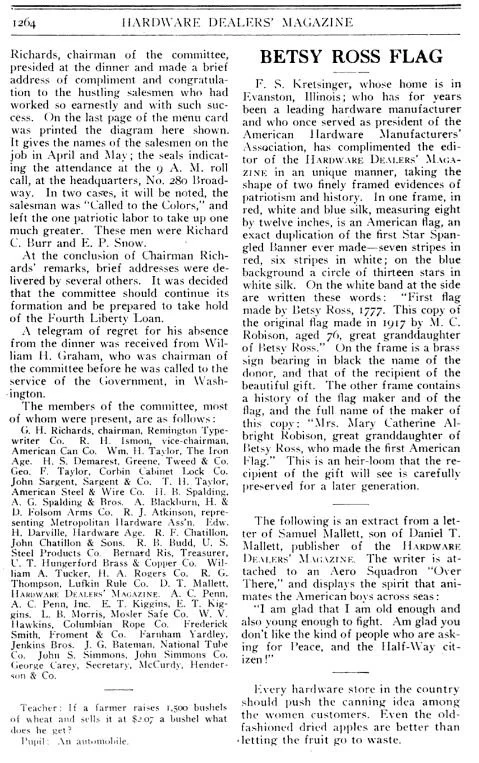

The flag was almost certainly made by Mary Catherine Albright Robison (1841–1932), great-granddaughter of Betsy Ross, and represents an important early example in the family’s effort to preserve and interpret their ancestor’s legacy. The date and dedication place it among the earlier of the documented “Ross-descendant” flags, produced decades before the design became common in commercial souvenir form.

MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION

The flag is constructed of fine silk, measuring approximately 29½ × 47¼ inches. The thirteen stars are hand-embroidered directly onto the blue silk canton in ivory silk floss, arranged in the circular configuration long associated with Betsy Ross.

Each star was executed by hand in a tightly worked satin stitch, a classic embroidery technique in which long, parallel stitches are laid side-by-side to form a smooth, lustrous surface. The satin stitch produces the dense, reflective texture visible here and was the preferred method for fine hand embroidery in the early 1900s. The subtle variation in stitch direction and tension from arm to arm confirms that the work was done by hand rather than by machine, whose motion would have produced uniform zigzag or chain patterns.

Under magnification, the thread shows the soft, irregular sheen of hand-tensioned silk, with the centers of the stars converging into tiny rosettes where the arms meet. These characteristics, along with the balanced thread weight, place the work squarely in the skilled domestic embroidery tradition maintained by the Ross descendants.

The stripes—seven red and six white—are machine-stitched, with narrow, evenly spaced seams typical of treadle sewing machines of the period. The hoist inscription, in white silk embroidery, is likewise worked by hand. Each letter follows the rhythm and spacing of Robison’s handwriting, functioning simultaneously as a dedication and a maker’s signature.

This combination of machine-sewn structure and hand-embroidered symbols—the stars and text—matches the construction of other known family-made examples, uniting craft precision with the symbolic continuity of the Betsy Ross legacy.

THE INSCRIPTION AND ITS CONTEXT

The flag memorializes Colonel Simon Winfield Scott (1832–1906), a Civil War veteran and first president of the Washington Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. Scott died in Seattle on July 18, 1906, and the flag’s July 20 date corresponds to memorial observances that followed his death.

Simon W. Scott was a figure of national and local prominence. Before the Civil War he was involved in early engineering work on the Panama Canal. He later organized and commanded the Seventh New York Regiment, serving in several engagements. Following the war, he acted as Indian Agent to the Sioux Reservation, where he served as custodian of Chief Joseph after his capture by General Miles.

By the 1890s, Scott had settled in Seattle, serving as land and tax agent for the Pacific Coast Company and as president of the Washington Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. His death in 1906 brought tributes from across the Pacific Northwest. The memorial flag presented here may have been produced either for the SAR’s use at those memorial events or as a gift from Robison’s DAR chapter, linking the family of Betsy Ross with one of the leading patriotic figures of the Pacific Coast.

Scott’s obituary in The Tacoma News Tribune praised his long career as an engineer and Indian agent, his command of the Seventh New York Regiment, and his civic leadership in Seattle. The inscription therefore connects two branches of patriotic lineage: the SAR, representing hereditary descent from Revolutionary soldiers, and the Ross family, descendants of the woman credited (albeit incorrectly) with sewing the nation’s first flag.

Mary Catherine Robison was an active member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) in Iowa, listed in early chapter rosters as Mrs. M. Katherine Robison. Her DAR membership would have placed her in regular contact with SAR figures such as Scott. The creation of this flag—likely commissioned or sent for memorial display—reflects the shared network of Revolutionary lineage organizations that flourished in the early 20th century.

MARY CATHERINE ALBRIGHT ROBISON

Born in Pennsylvania in 1841, Mary Catherine Albright Robison was the daughter of Rachel Jones Wilson Albright (1812–1905) and Jacob W. Albright (1811–1888). Through her mother, she was the great-granddaughter of Betsy Ross, inheriting both the family lineage and the symbolic responsibility of preserving its story. The Albrights lived in and around Philadelphia and later in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, a region steeped in Revolutionary memory and civic patriotism.

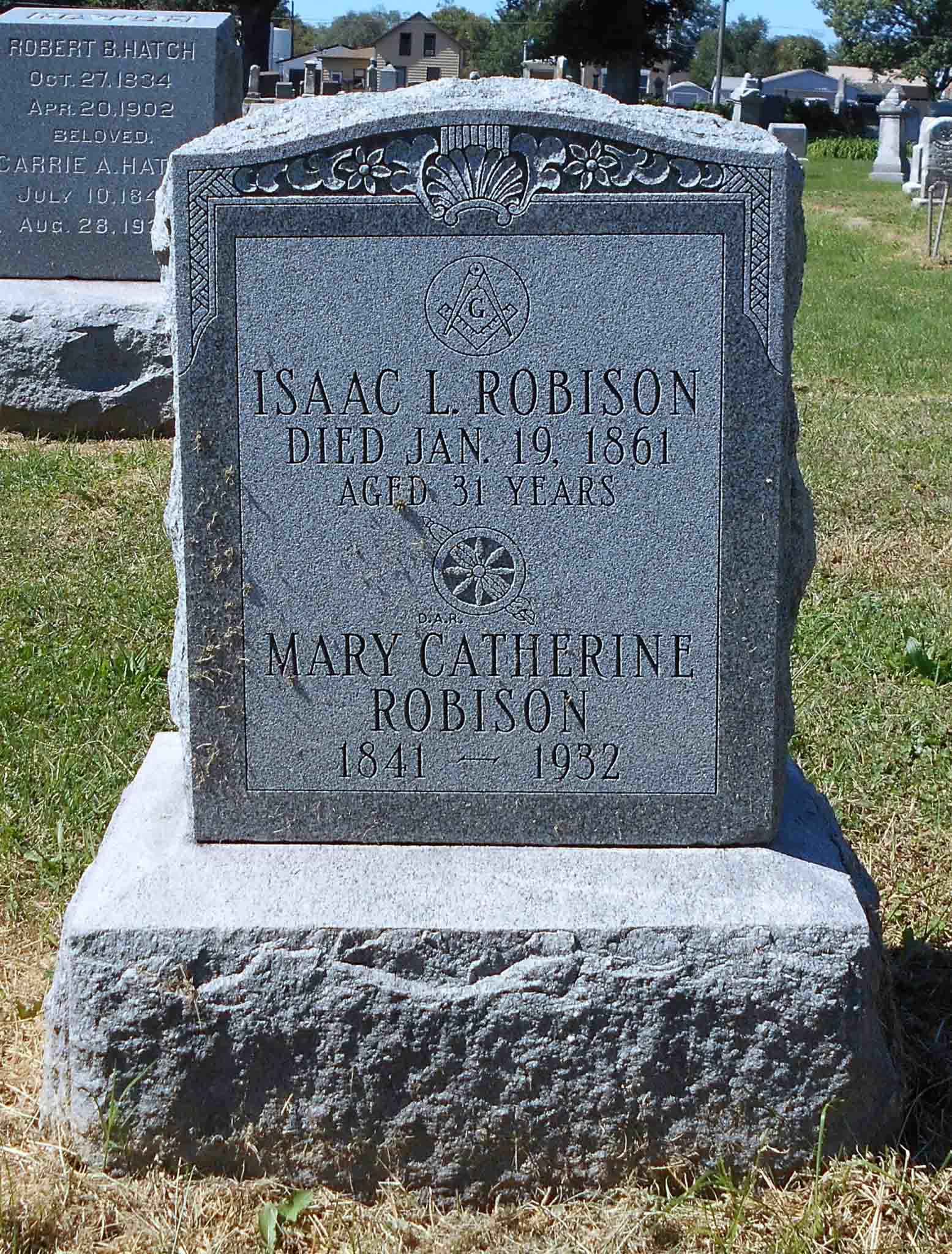

Mary Catherine married Isaac L. Robison (1830–1861), whose life was cut short when he died in his early thirties. Widowed young and without children, she returned to her family home, where she devoted much of her life to teaching, sewing, and to the family’s expanding public role as custodians of the Betsy Ross legacy. By temperament and circumstance, she was ideally positioned to continue her mother’s work—educated, precise, and deeply conscious of her ancestral connection to the flag.

Her mother, Rachel Jones Wilson Albright, was Betsy Ross’s granddaughter and one of the most active family members in promoting the Ross narrative. Rachel’s longevity—she lived to the age of ninety-three—bridged the early republic and the modern industrial age. She corresponded with patriotic groups, participated in the dedication of the American Flag House in Philadelphia, and became a recognized figure in the national press. Mary Catherine was by her side during much of this period, absorbing the public interest the story commanded and learning how to translate that legacy into tangible form.

Following her mother’s death in 1905, Mary Catherine assumed what can best be described as the family mantle. Between roughly 1903 and 1917, she produced a series of flags that echoed the design long associated with her great-grandmother. Most were made as small souvenirs or tokens of remembrance. Her flags often bore inscriptions identifying Robison as the maker and invoking her descent from Betsy Ross.

Each of her surviving works follows the same essential template: machine-sewn stripes paired with hand-embroidered stars and inscriptions. The structure reflects both tradition and adaptation—combining the precision of late nineteenth-century domestic sewing technology with the tactile authenticity of handwork. In this synthesis lies much of Robison’s artistic and historical significance: she modernized the family’s flagmaking practice without diluting its symbolic power.

Robison’s was an active member of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), appearing in early Iowa chapter rosters under the name Mrs. M. Katherine Robison. Her participation in the DAR not only affirmed her lineage but also gave her access to a wide network of women dedicated to patriotic education and commemoration. Within that circle, her connection to Betsy Ross carried considerable prestige.

Evidence suggests that she worked from her home well into her later years, producing flags for acquaintances, commissions, and exhibitions of patriotic handiwork. Surviving examples dated 1903, 1906, 1907, and 1917 demonstrate her consistent workmanship and adherence to a recognizable format. Her handwriting, which appears on multiple flags and in inked notes, remained steady and distinctive throughout her life.

By the time of her death in 1932, Mary Catherine had become the last living link to the direct Ross-descendant flagmaking tradition. Her work represents both a continuation and a culmination of that lineage. The flags she produced are not merely commemorative objects; they are expressions of personal devotion to a story her family had carried for more than a century—a story she quite literally kept alive with needle and thread.

HANDWRITING AND AUTHORSHIP

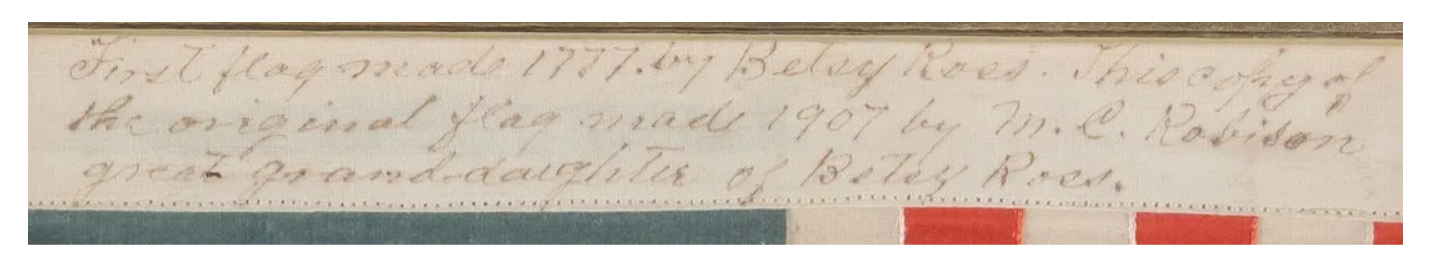

The embroidered inscription on this flag aligns exactly with the known handwriting of Mary Catherine Albright Robison. Two authenticated examples survive—one on a 48-star flag and another on a 13-star flag dated 1907—both bearing the same formula: “First flag made 1777 by Betsy Ross… made by M. C. Robison, great-granddaughter of Betsy Ross.”

Across all three, her handwriting is unmistakable: a right-leaning cursive with long horizontal t strokes, open-looped y and g, a rounded M, and consistent spacing between words. The embroidered text on the present flag reproduces those same letterforms—the formation of S in “Scott,” the upright W in “Washington,” and the terminal t in “Revolution.”

These consistencies confirm that Robison herself executed the inscription. The embroidery follows her handwriting with absolute fidelity, functioning as both record and signature.

BETSY ROSS AND THE FAMILY LEGACY

The story of Betsy Ross entered American public memory through her grandson, William J. Canby, who presented an account to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1870 claiming that his grandmother had sewn the first Stars and Stripes in 1776 at the request of George Washington. Though the historical record is ambiguous, Canby’s narrative—appearing at the height of the nation’s Centennial fervor—captured the imagination of a country eager for tangible connections to its Revolutionary past. Newspapers quickly circulated the story, and by the 1880s “Betsy Ross” had become a near-mythic figure, blending domestic virtue with patriotic service.

In the years that followed, Ross’s descendants became the stewards of that narrative, transforming oral history into a tangible, material tradition. Several branches of the family—the Wilson, Albright, and later Robison lines—undertook the making of small hand-sewn 13-star flags, which they sold, gifted, or presented at public events. These flags were often accompanied by handwritten notes or embroidered inscriptions identifying the maker as one of Betsy Ross’s grand- or great-granddaughters. Each was conceived not merely as a keepsake but as a physical link to the founding story itself—a symbol authenticated by bloodline and needle.

The family’s most active public advocate was Rachel Jones Wilson Albright (1812–1905), Ross’s granddaughter, who helped found and promote the American Flag House and Betsy Ross Memorial Association in Philadelphia during the 1890s. The Association purchased Ross’s former home on Arch Street, turned it into a patriotic shrine, and sold souvenir certificates and flags to fund its preservation. Rachel and her daughter Mary Catherine Albright Robison (1841–1932) produced many of the hand-sewn flags associated with this effort, both for the Association and for private commissions. Their flags—small, refined, and often made of silk—were prized as direct continuations of the Ross legacy.

These descendant-made flags carried enormous cultural weight. At a time when industrial production was rapidly replacing handcraft, they offered a reassuring image of continuity—linking the handmade origins of the nation’s first emblem to the new century’s mechanized world. The act of sewing, especially by women, came to symbolize patriotic virtue and ancestral authority. When Mary Catherine Robison embroidered the stars and inscription on the present flag in 1906, she was participating in that living tradition: reaffirming a lineage of both blood and craft that began with her great-grandmother.

By the early twentieth century, the market for “Betsy Ross flags” had expanded dramatically, with printed and machine-sewn versions sold to tourists in Philadelphia and beyond. Yet these commercial examples lack the authenticity and intimacy of the descendant-made pieces. Only a handful of flags produced by the Wilson-Albright-Robison family survive, most in small formats ranging from six inches to a foot in length. The larger silk examples—such as this one—are exceedingly rare, likely made for special presentation or memorial purposes rather than for sale.

Because so few of these early family-made flags survive, and because nearly all trace directly to one of these three family lines, each verified example offers tangible documentation of how the Ross legend was shaped, reinforced, and physically transmitted by her descendants. In that sense, this flag stands not only as a personal memorial to Colonel Simon Winfield Scott, but also as an heirloom of national mythology—stitched by a woman whose own hands carried forward the story that helped define the American flag itself.

PATRIOTIC SOCIETIES AND THE MEANING OF THE FLAG

By the early 1900s, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) and Sons of the American Revolution (SAR) stood at the center of the nation’s patriotic revival. Founded in 1890 and 1889 respectively, both organizations sought to preserve the ideals of the Revolution through education, civic service, and memorialization.

The DAR, composed of women directly descended from Revolutionary soldiers or patriots, focused on historic preservation, citizenship, and the commemoration of founding sites. The SAR, its male counterpart, emphasized lineage, veteran remembrance, and public celebration of national heritage. Together, they shaped the country’s early twentieth-century memory of the Revolution—raising monuments, marking graves, and sponsoring flag dedications.

CONCLUSION

The 1906 Robison flag holds exceptional importance within the continuum of Ross-descendant production. It embodies the intersection of family heritage, patriotic commemoration, and skilled craftsmanship. Its hand-embroidered stars and inscription, executed in her own handwriting, attest not only to her authorship but to the enduring symbolic power of the flag her ancestor made famous. Few surviving artifacts speak so directly to America’s interwoven histories of family, craft, and national identity.

Conservation Process: This flag was hand sewn to cotton fabric, and both were hand sewn to a mounting board. To prevent the black dye in the cotton fabric from seeping into the flag, it was first washed in a standard wash and then in a dye setting wash. The flag is positioned behind Optium Museum Acrylic.

Frame: The flag is presented in a deep, black-painted frame with a softly scooped profile and a lightly weathered surface that reveals subtle undertones of warm brown beneath the finish. The design is both substantial and refined, with a gently burnished texture that complements the age and character of the flag.

Condition Report: The flag survives in excellent condition for its age and material. The silk retains strong color throughout, with the red and blue tones vivid and stable. The white stripes show only minor age toning and scattered, light marks typical of early silk display flags. A few small, faint surface spots appear within the canton and along the lower field but do not detract from presentation. The embroidery remains bright, tight, and unmarred, with no thread loss or fraying evident.

Collectability Level: The Extraordinary – Museum Quality Offerings

Date of Origin: 1906

Number of Stars: 13

Associated War: Pre-Civil War

Associated State: Original 13 Colonies