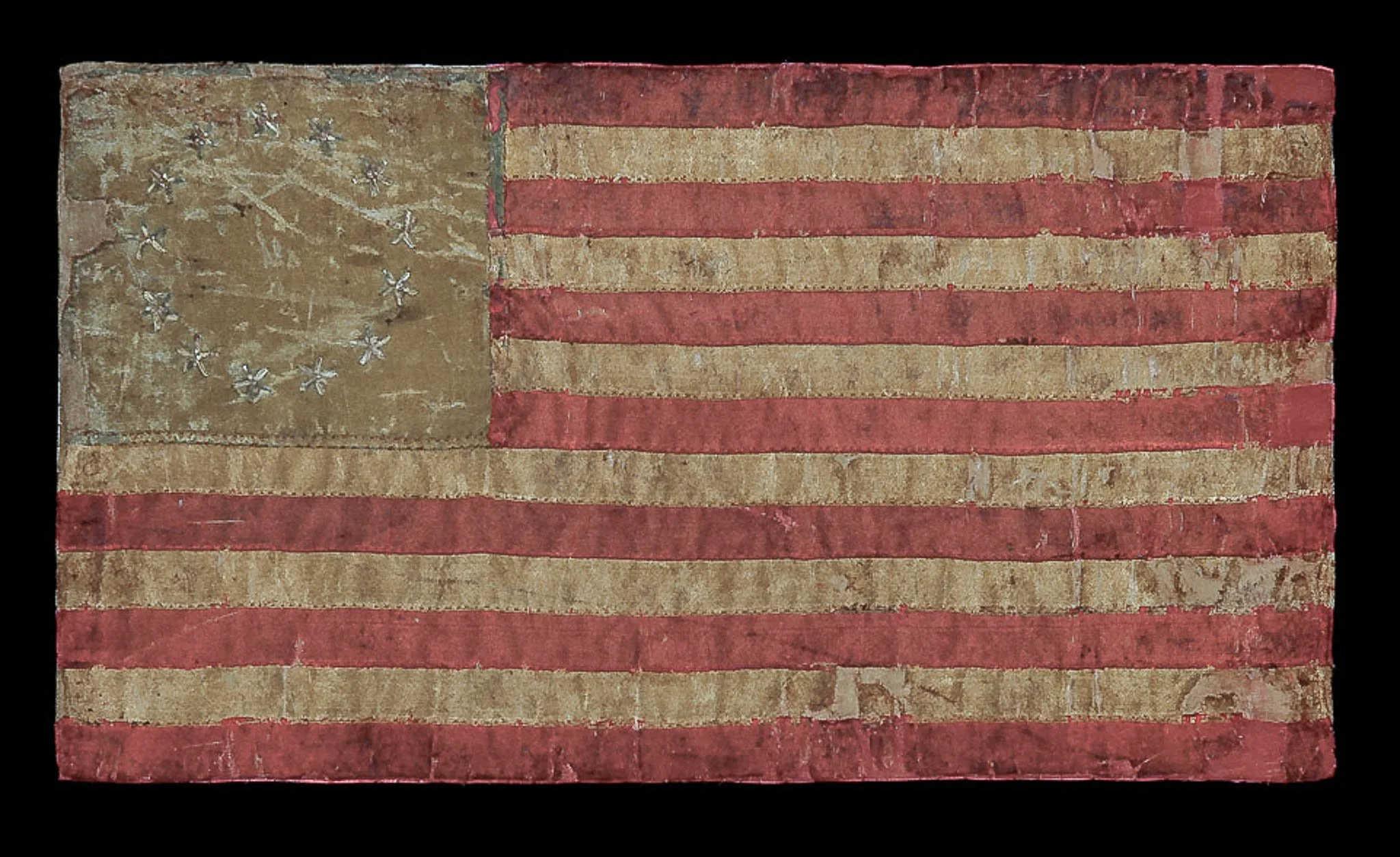

13 Star Antique Flag | Made by Descendants of Betsy Ross in Independence Hall | Features the Iconic Betsy Ross Pattern | Circa 1895–1913

13 Star Antique Flag | Made by Descendants of Betsy Ross in Independence Hall | Features the Iconic Betsy Ross Pattern | Circa 1895–1913

Frame Size (H x L): 13.25” x 17.25”

Flag Size (H x L): 5.75” x 10.25”

Offered is a thirteen-star American flag dating to the period between 1895 and 1913. Its stars are arranged in the widely recognized “Betsy Ross” pattern—a circular configuration of thirteen stars representing the original colonies. The circular formation has often been interpreted as a symbol of equality among the states, with none placed above or below the others. While this symbolism was likely assigned after the fact, it added to the pattern’s appeal in the American imagination and helped reinforce its association with democratic ideals and Revolutionary unity.

Betsy Ross is often mistakenly credited with having made the first American flag, a claim that continues to appear in popular culture and elementary education. While she undoubtedly made flags during the Revolutionary era and deserves credit for her role in early American textile production, there is no surviving documentation—such as letters, journals, or contracts—that substantiates the story that she designed or sewed the first national flag.

Modern historians generally attribute the design of the first official flag to Francis Hopkinson, a member of the Continental Congress, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and practicing attorney. In 1780, Hopkinson submitted a request to Congress for compensation for designing what he referred to as “the flag of the United States of America.” He first sought payment in the form of “a Quarter Cask of public wine,” due to the depreciation of currency, and later requested $1,440 in Continental paper. While no payment appears to have been issued, his request provides concrete documentary evidence linking Hopkinson to the flag’s design—something absent in the case of Betsy Ross.

WILLIAM CANBY

It was not until 1870—nearly a century after the flag was designed—that the myth of Betsy Ross took hold. At that time, William Canby, the grandson of Betsy Ross, told the Historical Society of Pennsylvania that she designed and made the first flag at George Washington’s request. One of the earliest—if not the earliest—media accounts perpetuating the myth was in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1873. Its account was as follows:

The construction of the first national standard of the United States, as a design, from which the “Stars and Stripes” was afterword adopted, took place under the personal direction of General Washington, aided by a committee of Congress “authorized to design a suitable flag for the nation,” at Philadelphia, June, 1777.

This took place at the residence of Mrs. Ross, a relative of Colonel Ross, in Arch Street, between Second and Third, where General Washington and the committee completed the design, and employed Mrs. Ross to execute the work. The house is still standing (No. 239). Mrs. Ross was afterward Mrs. Claypoole. Her maiden name was Griscom, and, according to the fashion of the times, she was called “Betsy.”

Betsy Griscom had, before the Revolution, acquired some knowledge of the “upholder” trade, as it was then called—an occupation synonymous with that of the modern upholsterer—at the time mentioned was carrying on business on her own account in her little shop. One day, probably between the 23rd of May and the 7th of June, 1777, during which period Washington was in Philadelphia, there came to her the commander-in-chief, the Hon. George Ross, and other gentlemen, members of Congress, who desired to know whether she could make them a flag according to a design which they would produce. She intimated her willingness to try. The design was for a flag of thirteen red and white stripes, alternate, with a union, blue in the field, spangled with thirteen six-pointed stars. Mrs. Ross expressed her willingness to make the flag, but suggested that the stars would be more symmetrical and pleasing to the eye if made with five points, and she showed them how such a star could be made, by folding a sheet of paper and producing the pattern by a single cut. Her plan was approved, and she at once proceeded to make the flag, which was finished the next day. Mrs. Ross was given the position of manufacturer of flags for the government, and for some years she was engaged in that occupation. The business descended to her children, and was carried on by her daughter, Clarissa Claypoole, who voluntarily relinquished it on becoming a member of the Society of Friends, lest her handiwork should be used in time of war.

CANBY’S SUPPORT (OR LACK THEREOF)

Canby’s claim, however, lacked corroborating historical evidence. His assertions rested solely on family affidavits—accounts passed down orally and recorded well after the fact. These documents are both self-interested and historically unreliable. From firsthand experience evaluating antique flags, we can attest to the frequency with which family lore conflicts with the physical characteristics and construction of a flag. As just one example, we corresponded with a family who believed their flag dated to the 18th century, when in fact the stitching clearly indicated a mid-19th-century origin.

Despite this lack of evidence, the Betsy Ross narrative gained widespread acceptance in the public imagination. The years following the Civil War were marked by a surge in patriotic sentiment, culminating in the Centennial celebrations of 1876. The country, eager to reconnect with its founding ideals, embraced stories that symbolized unity, sacrifice, and national pride. In that environment, the Ross legend became a powerful—and appealing—symbol of Revolutionary womanhood and early American ingenuity.

RACHEL ALBRIGHT AND SARAH WILSON

While Canby introduced the narrative, it was Betsy Ross’s descendants—Rachel Albright (granddaughter) and Sarah Wilson (great-granddaughter)—who popularized it on a broader scale. Between approximately 1895 and 1913, they sewed and sold thirteen-star “Betsy Ross” flags from a room in the east wing of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Priced at just a few dollars, these flags were marketed as replicas of the “original flag” sewn by Ross.

This commercial enterprise capitalized on the growing appetite for patriotic memorabilia and educational iconography. During this period, flag history was being institutionalized in classrooms and public exhibitions. By offering physical representations of the story within the very walls of Independence Hall, Albright and Wilson helped transform a loosely documented family narrative into a widely accepted national myth.

The flag offered here is one such example, almost certainly made by either Albright or Wilson. Their flags share distinct and consistent characteristics: red and white silk ribbons for the stripes, a blue silk canton, hand-embroidered stars formed from silk floss in a spoke-like pattern, and a high degree of craftsmanship that stands apart from most other surviving flags of the period.

Some Albright/Wilson flags were inscribed directly on the hoist. One such inscription read: First flag made in 1777 by Betsy Ross. This copy of the original flag made in 1903 by Rachel Albright, grand-daughter of Betsy Ross, aged 90 years 10 months. Others were accompanied by paper notes that conveyed similar messages. The flag offered here likely fell into that latter category, but the note has since been lost—a common occurrence, with notes surviving on only about 5% of known examples.

RARITY

Despite its prominence in popular culture, the Betsy Ross pattern is among the rarest of all antique thirteen-star designs. In our experience, roughly 75% of thirteen-star antique flags feature the 3-2-3-2-3 arrangement, around 20% display the medallion configuration, and only a small remainder—including the Betsy Ross circle—fall into more uncommon patterns.

Flags made by Albright and Wilson are particularly scarce. When they do surface, they tend to enter institutional or top-tier private collections.

THIRTEEN-STAR FLAGS GENERALLY

The original thirteen-star flag was officially adopted by the Continental Congress on June 14, 1777. The resolution read: “Resolved, that the flag of the United States be made of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white, that the union be thirteen stars, white on a blue field, representing a new constellation.” Although replaced as the official design in 1795, the thirteen-star flag remained in use for symbolic and ceremonial purposes throughout the 19th century.

Small U.S. Navy boats flew it as an ensign until 1916. It was also displayed at George Washington’s funeral in 1799, during the 50th anniversary celebrations of American independence in 1824, and in honor of General Lafayette’s 1824 return tour of the United States. Later, it appeared during both the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) and the Civil War (1861–1865), periods in which patriotic symbolism was particularly potent. Thirteen-star flags were also prominent during the Centennial celebrations of 1876, especially at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

Conservation Process: The flag has been professionally conserved, mounted to silk, and is now protected behind Optium Museum Acrylic to ensure long-term preservation.

Frame: Constructed from tiger maple, the frame dates to the mid-1800s and features natural striping in the grain. Its simple, square-edged design reflects the craftsmanship of the period.

Condition Report: The flag shows clear evidence of age, with significant surface wear, fabric splitting in portions, and visible deterioration to both the canton and stripes. There is fading throughout, along with scattered losses—particularly along seam lines and edges—yet the circular star pattern remains intact and recognizable. These elements have been stabilized through professional conservation.

Collectability Level: The Best – Perfect for Advanced Collectors

Date of Origin: 1895-1913

Number of Stars: 13

Associated State: Original 13 Colonies